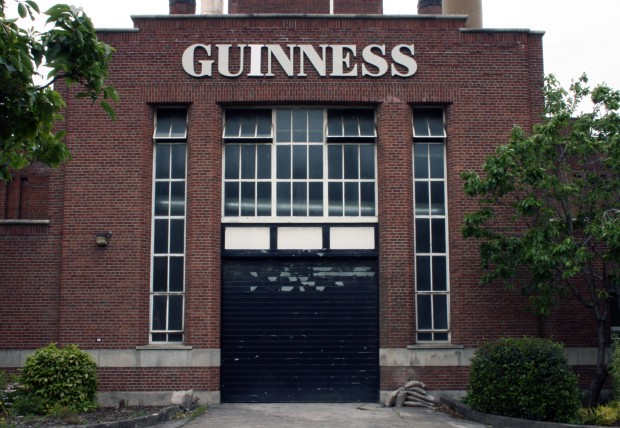

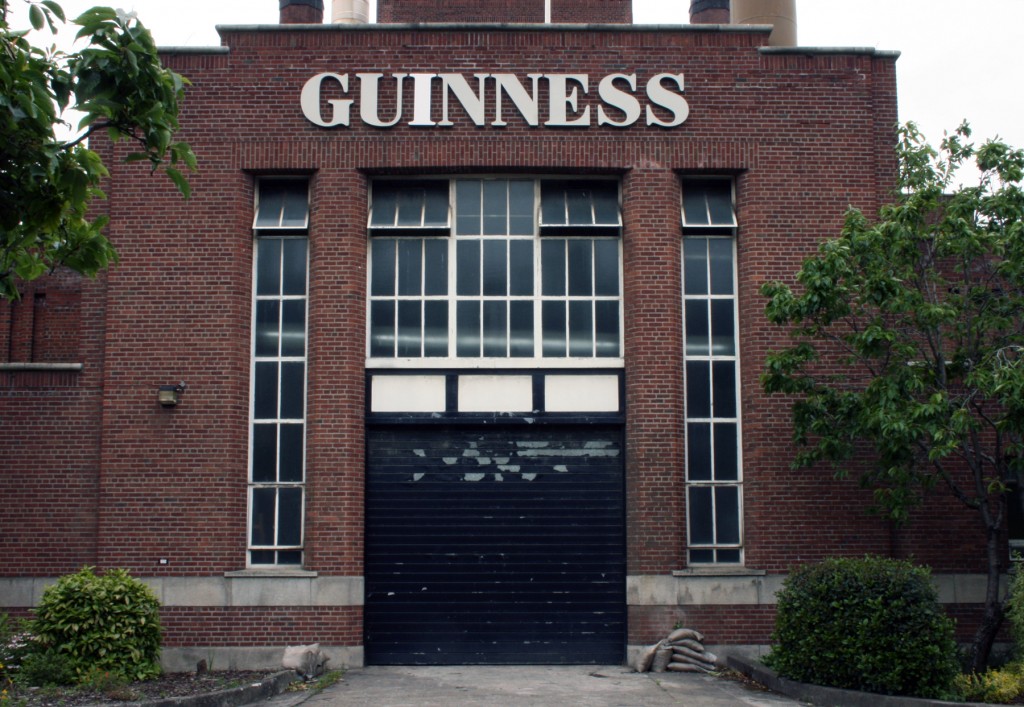

Though the Power House at Guinness faces the street to the south at St. James’s Gate, a number of descriptions refer to the north elevation to the Liffey far below as the main elevation. Either way seems to make sense and looks well composed, though it’s interesting as an acknowledgement of the elevation of the site relative to the river.

The building was designed by F.R.M. Woodhouse, an English architect, and is also credited to Sir Alexander Gibb & Partners by Christine Casey’s Dublin (p.651). It was constructed between 1946 and 1948, though Woodhouse himself died in 1946. The project was part of an extensive modernisation programme at Guinness from after the war (which had delayed plans since 1939) into the early 1950s, and the power house is identified as a significant part of this plan, originally designed to produce electricity and pressure steam from oil and coal.

From the south, the building appears to be symmetrical, though the aerial view suggests the upper section of the left wing on the front plane is false, wrapping around to match its counterpart on the right but not enclosing an interior space. This low section with the raised central bays extends back with a flat roof to meet a higher block with its centre rising like a tower, and to the rear, there’s a pair of two tall brick chimneys. (If your eyesight is better than mine and you’re committed to this river elevation, reverse it, but you’ll miss out on the false section.)

One wonderful quality in newspaper reports on new buildings is the stream of numbers, presumably just impressive but near-meaningless to most of the audience. This one doesn’t disappoint: “a million Kingscourt bricks, 700 tons of structural steelwork and 800000 cubic feet of reinforced concrete went into the construction of the power-house.” (‘New Power House completed’, The Irish Times, May 24 1950, p.4) The brick is harmonious with many of the older Guinness buildings to the south, and there’s an elegance in the building’s vertical lines against the light horizontals of the brick courses. Throughout the brickwork, the details around openings and at the parapet are quite subtle and smart.

It’s a beautiful building, and refined and compact in a way that you might associate with offices if it weren’t for the narrow windows and the bloody big chimneystacks in behind. Compared to some of the late 1920s and 1930s work I’ve been looking at recently, it’s notable how the style feels borrowed from a decade or more earlier, but it’s beautiful nonetheless.