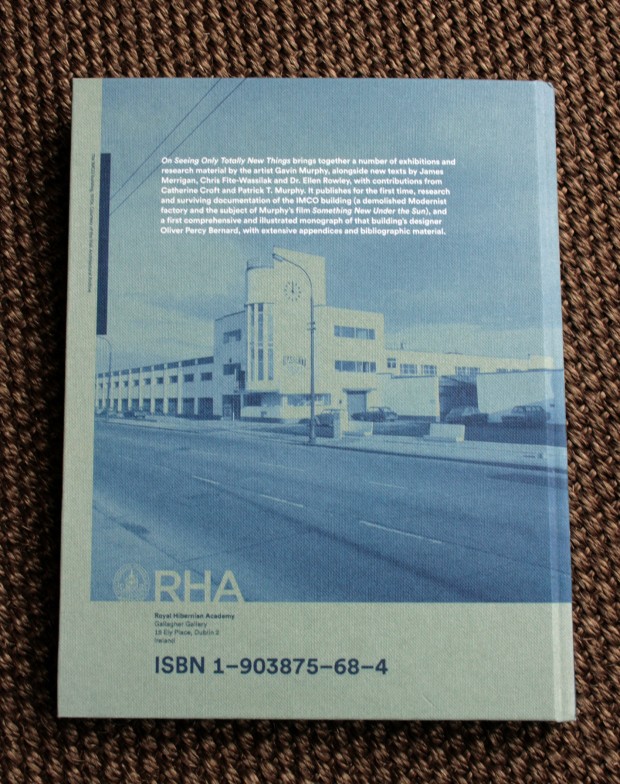

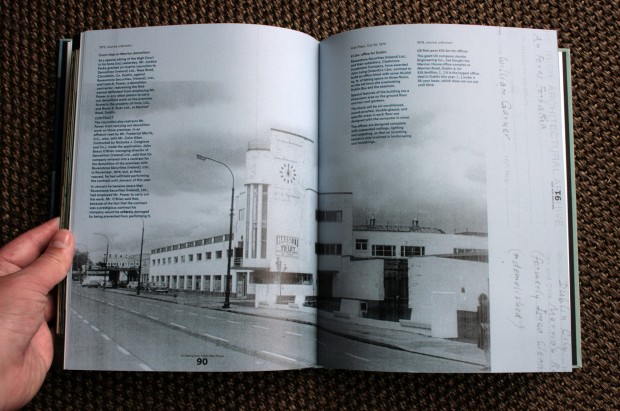

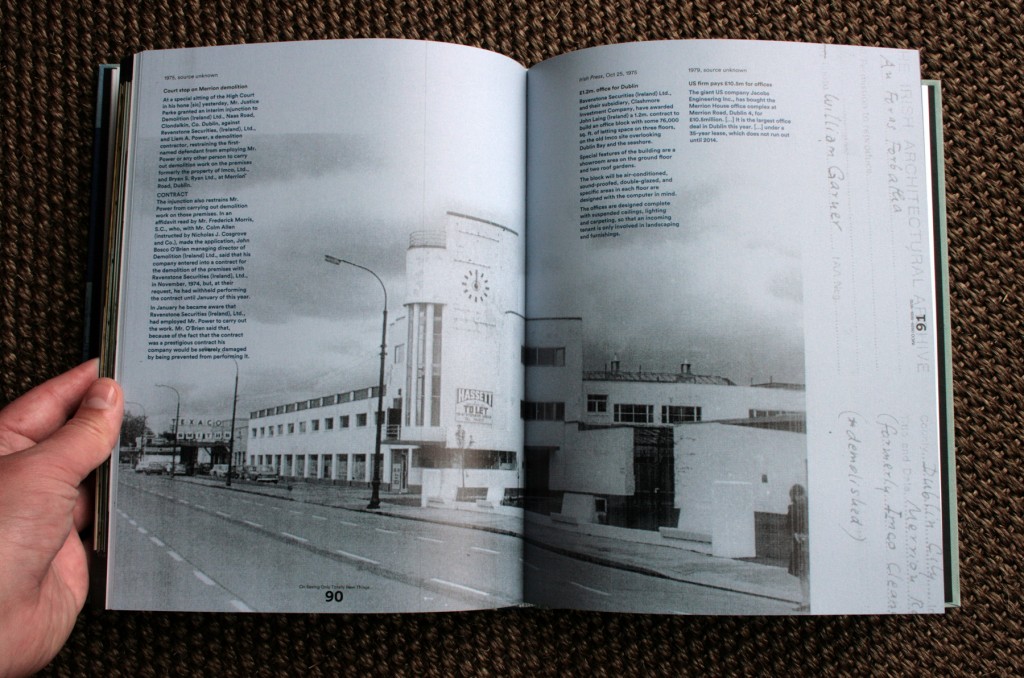

Dublin’s IMCO complex was located on Merrion Road for about 35 years. It was built in phases, though the most recognisable and remembered element is the extension and tower designed by Oliver Percy Bernard, with Higginbotham & Stafford – a smooth, white modern addition that made the building something of a landmark.

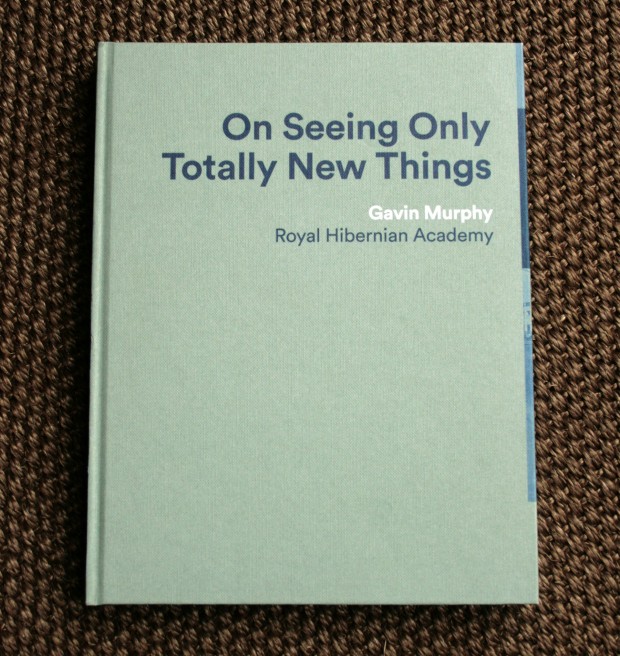

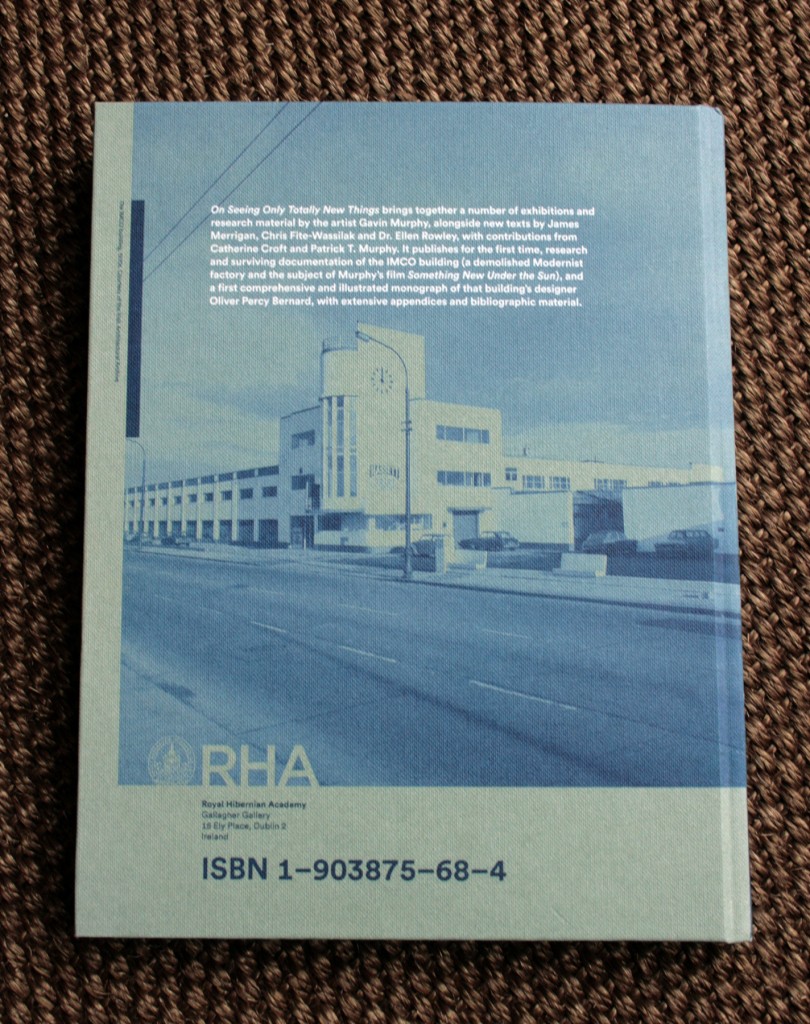

Gavin Murphy‘s On Seeing Only Totally New Things is a gorgeous book with the IMCO complex at its core. Within, there are a series of texts by other contributors (by Patrick T. Murphy of the Royal Hibernian Academy, James Merrigan, Dr. Ellen Rowley, Catherine Croft, Chris Fite-Wassilak), as well as documentation of three of Murphy’s recent exhibitions (including the film Something New Under the Sun, bringing Bernard and IMCO to eva International and the RHA in 2012), a book-within-a-book in which Murphy examines Bernard’s career, and a collection of ephemera, artefacts, and photographed texts around the subject. There’s a very successful breadth to the project, speaking at once to Murphy’s judgement, ambition, and detective work, and also to the value of a building’s story being approached by someone whose practice is not pure architecture or architectural history. It feels like an expanded archive, driven by both personal and intellectual curiosity, and it’s genuinely exciting as a reader to be presented with the outcome.

Looking from a purely architectural perspective for a second, there are three particularly strong draws within the book. Ellen Rowley’s text sweeps through the context of modernity in Ireland (quoting Fintan O’Toole describing it as “a half-finished project” between the pre-modern and the post-modern), setting the IMCO building within this landscape and locating its position within the tradition. It’s a nice text, doing a good job balancing the appeal and interest of the building as one of a type, while (rightly) not presenting the IMCO complex as one of the world’s greatest buildings – maybe it’s particularly resonant to me as it’s one of the central elements of Built Dublin, but it’s very possible for something to capture the imagination and be interesting and worthy of love without it being necessarily notable within the architectural canon, say.

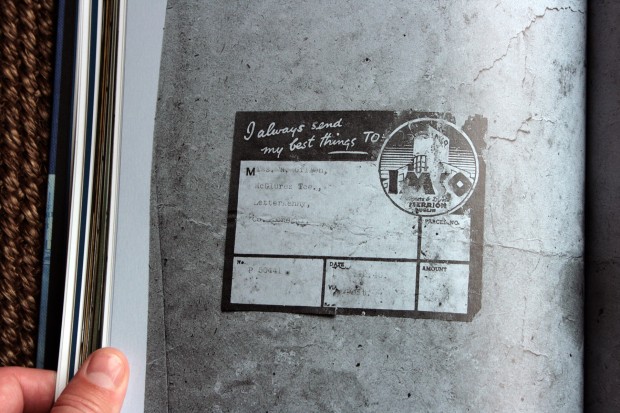

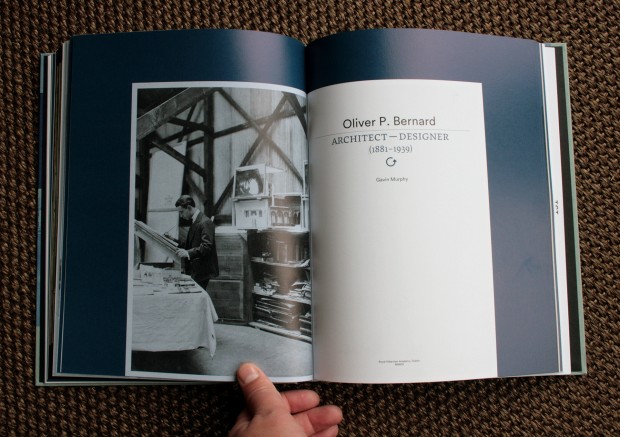

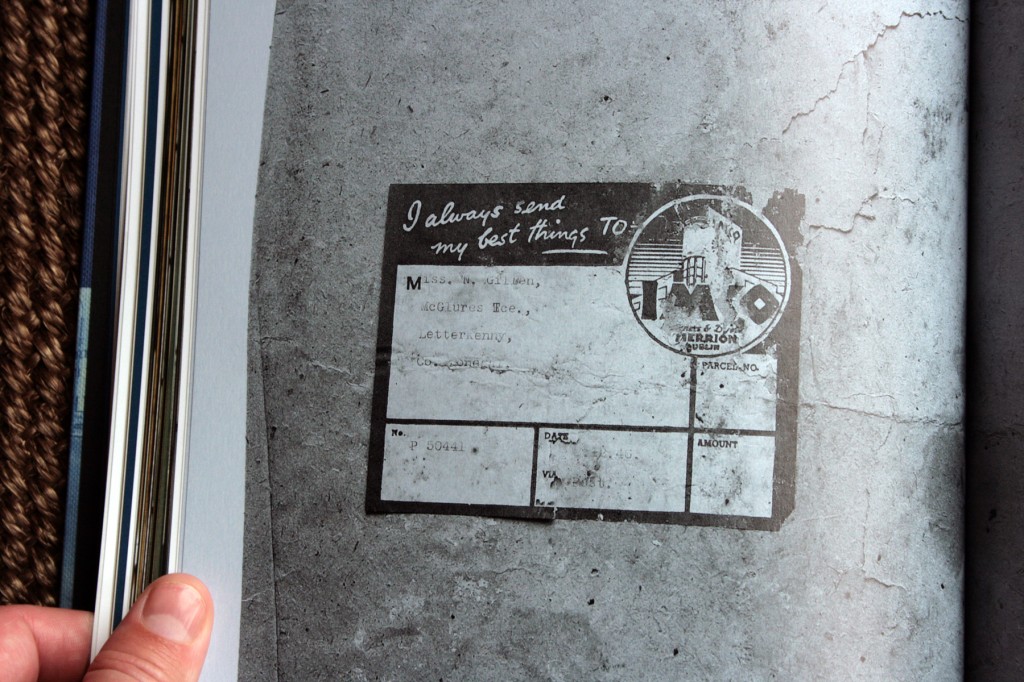

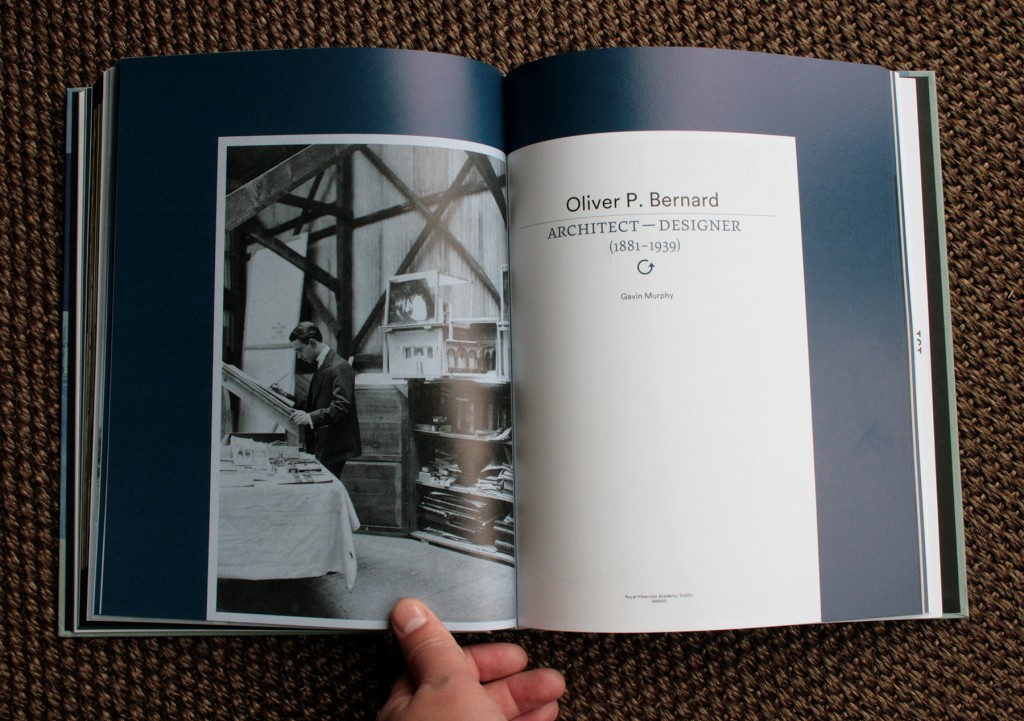

Secondly, there’s Murphy’s piece on Bernard’s life and work, an amazingly colourful and eventful story from being orphaned at an early age to surviving the sinking of the Lusitania. Bernard’s design work crossed from theatrical to interior to furniture to architecture, with a particularly interesting period in the 1920s and 30s working for J. Lyons & Co, and there are plenty of drawings and photographs documenting his projects. Thirdly, there’s the documentation of archive material and ephemera – if you’ve spent time researching Irish architecture, you’ll have the added pleasure of recognising handwritten catalogue numbers and bookshelves in the Irish Architectural Archive or a sticky-tabbed copy of Paul Larmour’s Free State Architecture, but anyone will find fascination reading the story through newspaper clippings and archive photographs. Right at the back, there’s a huge density of material just where you’re expecting a sober appendix, and it adds to the feeling of completion, like it’s generously encapsulating the project and bringing the whole lot together for us.

During the building’s original construction, there were objections due to its obstruction of the view to Dublin Bay and Howth from Sandymount, but it appears there was less of a fuss on its demolition. There’s an interesting parallel here to Bernard’s own work – he’s quoted as saying that “an up-to-date hotel should covey to every patron an impression of recent completion, as if it had only just opened its doors to the public.” Here, there’s something we see throughout the book, from the observation that demolition is part of the modernist architectural cycle, to a quote from PLAN magazine (March 1977) at the end of Rowley’s text: “…a new office building has arisen from the dust of the demolished IMCO building. (General public interest in buildings has not as yet staggered past the Victorian suburb period so voices raised against its demolition were crying in the wilderness.)” Rowley is a co-founder of Docomomo Ireland, and for anyone in Docomomo or of a similar sympathy, it can still seem a bit like general public interest is lagging a long way in the past. There’s an excerpt also from a presentation by Catherine Croft (Director of the Twentieth Century Society) about how we value buildings and how the material thing matters – “the material fabric of the building does actually embody all sorts of messages, ones that we can see now and ones that future generations might interpret that we have no way of predicting what they might be.” It’s a core question for any conservation debate, but while the IMCO complex was materially erased by an office block, the book brings together so much of its resonance and its life that it makes the building feel real and like a thing that existed, in a way that can be hard to conjure once something is passing from memory.

It should be extremely evident from the photographs, but the book’s design is beautiful – there’s at least another reading where you just flip the pages and enjoy how well it sits together, with the exhibition photographs presented large and rich, the texts and documents bedded together harmoniously without anything being compromised for cohesion, and the treatment of the book-within-a-book for Bernard’s biography. The publication was designed by Atelier.

Thanks to Gavin Murphy for the copy of his beautiful book. If you’re looking to purchase one, you can try contacting the Royal Hibernian Academy (+353 1 661 2558 or info@rhagallery.ie) or dropping into the RHA in Dublin, or else contact Gavin himself through his website. Worth seeking out!