At the most recent City Intersections event on Smart Dublin, one of the three brilliant speakers was Mary Mulvihill of Ingenious Ireland, who ran through a series of examples of ingenuity that happened in Dublin. It led to a discussion about the perception of Ireland, and how this aspect is often missing from it, and how to communicate this. (It probably goes without saying that I’m very interested in these questions.)

I’d photographed the diving bell on Sir John Rogerson’s Quay a while ago, and it came up in Mary’s talk and the ensuing discussion. As a part of the city, it’s a big hulking red object presented without explanation, a little too practical and worn-looking to be sculptural, a little too plinthed to be in use. As an object, I find it gorgeous: the weathering has given it incredible texture and colours when you get close up, the grilles at the side conjure up something simultaneously jaunty and grim, and the rivets and the ladder steps suggest the hard, fearless culture of dock work.

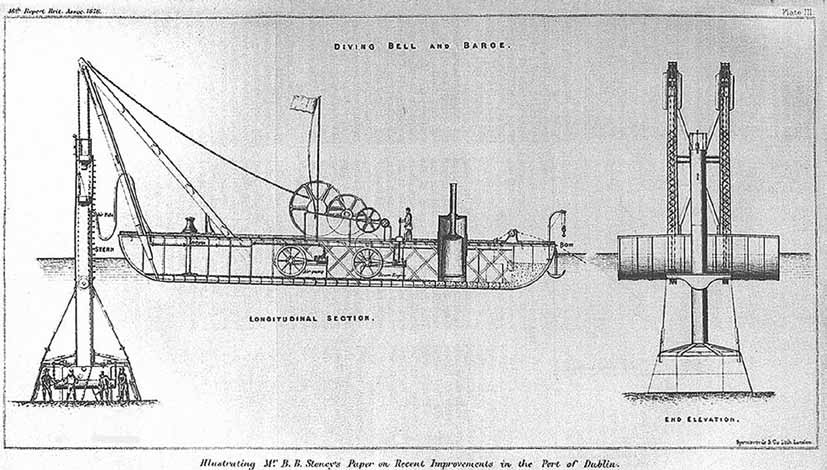

It’s evocative, but the explanation is even more interesting. The diving bell has a very long history as the ultimate in claustophobia triggers – an underwater chamber full of air, allowing for work on the bed of a river or sea (and later developed to incorporate systems of replenishing fresh air). During his tenure as Chief Engineer to the Dublin Ballast Board (later Dublin Port and Docks Board), Bindon Blood Stoney devised a method of construction for the quays, using huge prefabricated concrete blocks (made on the wharf) instead of hand-laying stone in a cofferdam system. The bed was prepared for the blocks by levelling it, first by dredging and then by workmen laying gravel. These gravel-layers worked inside a special diving bell designed by Bindon Blood Stoney, and there’s a great history here in an essay by Cormac F. Lowth, ‘The Dublin Port Diving Bell’:

The bell chamber was twenty feet square and the access shaft with its airlock chamber was three feet in diameter. There was six and a half feet of headroom inside. The overall depth of the bell including the shaft and air-lock chamber was forty-four feet. The horizontal air pump, and the lifting gear on both barges were driven by steam engines mounted inside the barges. The surrounding water had a cooling effect on the air going to the bell chamber, nevertheless, men working in the bell chamber found the atmosphere oppressively warm.

Diving bell and float, image from http://www.mariner.ie/history/articles/engineering/the-dublin-port-diving-bell

The bell continued to be used into the 1950s, and thanks to a campaign to save it from being scrapped, the bell was moved to its current location in the 1980s, later restored (with support from the Dublin Docklands Development Authority and the Dublin Port Company) and with a hole cut in the side for a view into the hollow, open-ended volume. As you might suspect from examining it closely, the vertical shaft leading to the airlock is a replica – the incredibly textured surface of the other parts makes this look as smooth as PVC piping.

Back to the object. Within the context of the quays as an open space, the diving bell feels like a successful cue to the near-invisible history of construction and commerce in a place that’s now a little bit empty – much more evocative and affecting than any monument could be, especially as you stand beside it and imagine such a confined space surrounded by water. I’ve often walked down to it with no other purpose.

There’s a difficult thing in presenting history within the city’s fabric, and though this is an artefact of building Dublin rather than built Dublin, it raises a few of the aspects that interest me about this. Putting plaques all over the city adds to the visual noise and often diminishes the subject, never mind reducing things to dates or names. On the other hand, I often wish huge infrastructural projects, especially historic ones, would include some reference to how many (if any) lives were lost during their construction. It’s easy for me to think of parts of the city like bridges or quays or canals as being there forever, unimaginable as a human feat and barely imaginable as one with mechanical and technological assistance, but there’s invisible stories behind them, and along with the usual questions of power and money, there were dozens or hundreds of people doing high-risk, low-paid labour to make them happen. I’d like not to be allowed to forget that.

The question of smartphones came up on Tuesday, and they’re inadequate as a total solution (as, obviously, only some people have them) but they can offer something that plaques can’t: particular strands of history or urban detail. Major textbook events, radical history, minority histories, architectural history, materials, science, popular culture, everything can be added as an accessible layer if you can pull a virtual Dublin into the physical one. Guided tours do a great job of adding these layers – and here we’re back to Mary Mulvihill, who does this in several forms – but the mystery is back once they’ve passed.

Bindon Blood Stoney might be the best-named man in engineering history and it seems a pity that anyone in Dublin, as a visitor or resident, might miss the chance to hear about him. At the same time, this is one of the best features along the quays and campshires, and there’s something to be said for the evocative puzzle.